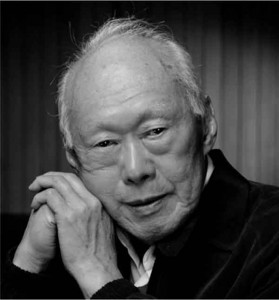

Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who was Singapore’s first Prime Minister when the country gained Independence in 1965, has died on Monday (Mar 23) at the age of 91.

“The Prime Minister is deeply grieved to announce the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore. Mr Lee passed away peacefully at the Singapore General Hospital today at 3.18am. He was 91,” said the PMO.

Arrangements for the public to pay respects and for the funeral proceedings will be announced later, it added.

Here are some of the highlights of his life story. Long read but a very good read to see what Mr Lee has done for Singapore.

Mr Lee, who was born in 1923, formed the People’s Action Party in 1954, then became Prime Minister in 1959. He led the nation through a merger with the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, as well as into Independence in 1965.

He leaves behind two sons – Lee Hsien Loong and Lee Hsien Yang – and a daughter, Lee Wei Ling.

HIS EARLY YEARS

From early in his life, Mr Lee Kuan Yew had braced himself to face history’s tumultuous tides head-on.

His efforts to build a nation were shaped by his early life experiences.

For the young Lee Kuan Yew, the Japanese Occupation was the single most important event that shaped his political ideology. The depravation, cruelty and humiliation that the war wreaked on people made it clear to Mr Lee that, to control one’s destiny, one had to first gain power.

Born to English-educated parents Lee Chin Koon and Chua Jim Neo, Mr Lee was named “Kuan Yew” which means “light and brightness”, but also “bringing great glory to one’s ancestors”. He was given the English moniker “Harry” by his paternal grandfather.

He continued the family tradition of being educated in English, and read law at Cambridge University after excelling as a student at Raffles College. His experience of being as a colonial subject when he was in England in the late 1940s fuelled his interest in politics, while also sharpening his anti-colonial sentiments.

He said later: “I saw the British people as they were. They treated you as colonials and I resented that. I saw no reason why they should be governing me – they’re not superior. I decided, when I got back, I was going to put an end to this.”

Mr Lee’s political life began right after he returned to Singapore in 1950, when he began acting as a legal adviser and negotiator representing postal workers who were fighting for better pay and working conditions.

He was soon appointed by many more trade unions, including some which were controlled by pro-communists.

In a marriage of convenience to overthrow the British, Mr Lee formed the People’s Action Party in 1954 with these pro-communists and other anti-colonialists.

THE BATTLE FOR MERGER

A key part of winning power at the time was securing the support of the masses, and this meant reaching out to the Chinese-educated, which made up the majority of the population in Singapore. He had taken eight months of Mandarin classes in 1950, and he renewed his Mandarin education five years later, at the age of 32. And within a short time, he had mastered the language sufficiently to address public audiences.

In the mid-1950s, riots broke out that fuelled tensions between the local Government and the communist sympathisers in the Chinese community. A few pro-communist members of the PAP were arrested.

Leading the PAP, Mr Lee fought for their release and ran a campaign against corruption in the 1959 elections for a Legislative Assembly. The PAP won by a landslide, and Mr Lee achieved what he had set out to do – Singapore was self-governing, and he was Prime Minister.

But there were others who would contest the power he acquired, and they had different political agendas. It became apparent that leading Singapore meant having to break ranks with some of his anti-colonial allies – the pro-communists.

Mr Lee said of the pro-communists: “They were not crooks or opportunists but formidable opponents, men of great resolve, prepared to pay the price for the communist cause.”

Mr Lee and his team were well aware of the hard fight they faced against the pro-communists, having seen up close how they could mobilise the masses through riots and strikes to paralyse a Government. And success in this fight depended a lot on Mr Lee’s leadership.

The battle-lines were drawn sharply over the proposal for merger with Malaysia – the non-communists were for it, and the pro-communists were against it.

There were compelling economic reasons for merger, but Mr Lee was also clear about its political necessity. To him, merger was absolutely necessary to prevent Singapore and Malaya being “slowly engulfed and eroded away by the communists”.

He believed that building a common identity between individuals on either side of the Causeway would propel them across racial and religious divides towards a common land. Part of this was making sure that people felt that they are wanted, and not “step-children or step-brothers, but one in the family and a very important member of the family”.

He campaigned relentlessly and tirelessly for merger, speaking over the radio, and in nearly every corner of Singapore. After an intense public contest that pitted him against his political opponents, Mr Lee won and most Singaporeans voted in favour of the union with Malaysia.

On Sep 16, 1963, which coincided with his 40th birthday, Mr Lee declared Singapore’s entry into the Federation of Malaysia.

But this did not mean an easy working relationship between the two sides, and serious differences emerged. Mr Lee wanted a “Malaysian Malaysia”, where Malays and non-Malays were equal, and he would not condone a policy that supported Malay supremacy.

Differences between the two sides grew – from conflicts between personalities and disagreements about a common market, to the PAP’s participation in Malaysia’s general election. Malaysian politicians considered it a breach of understanding for the PAP to take part in mainland politics.

Things came to a head over constitutional rights. Mr Lee addressed the Malaysian Parliament in May 1965, in both English and Malay, laying out his case against communal politics.

But a year after racial riots were sparked off by what Mr Lee called Malay “ultras”, creating a deep divide, Singapore separated from Malaysia on Aug 9, 1965. It was a time of great disappointment for Mr Lee, a moment which he said was one of “anguish” for him.

FROM MUDFLAT TO METROPOLIS

And so it was that Singapore became an independent state that day in 1965, but not by choice. The island’s 2 million people faced an uncertain future, and that uncertainty weighed heavily on the man who was leading it.

Left with no hinterland and hardly any domestic market to speak of, Singapore’s only option was for its leaders to fight hard for its survival.

And despite the daunting task that loomed ahead, Mr Lee chose to set his sights on building a country of the future, and he never veered from that vision. In his own words in September 1965: “Here we make the model multiracial society. This is not a country that belongs to any single community – it belongs to all of us. This was a mudflat, a swamp. Today, it is a modern city. And 10 years from now, it will be a metropolis – never fear!”

But this difficult task was soon made more challenging by another crisis. In 1968, Britain unexpectedly announced its intention to withdraw its troops from Singapore. Mr Lee and his team now had to confront the prospect of a country without its own security forces. Worse, thousands of workers retrenched from the British bases joined the already large numbers of unemployed in the country.

Mr Lee’s good ties with British leaders led them to extend the departure of their forces to the end of 1971. These military bases contributed 20 per cent to the economy and provided jobs for 70,000 people, and the extension of the pull-out date softened the blow to Singapore’s economy.

In the face of these looming challenges, Mr Lee and his team soldiered on to hold the fledgling country together, and to make it work. The vacated British naval bases were used to boost the economy, and efforts were made to attract investors to set up industries on the former British army land.

To survive what was then a hostile neighbourhood, Mr Lee adopted a two-pronged approach to grow the economy.

First, to leapfrog the region and link up with the developed world, for both capital and market initiatives; and second, to transform Singapore into a “first world oasis in a third world region”. With first-world standards of service and infrastructure, Mr Lee saw the potential for Singapore to become the hub for businesses seeking a foothold in the region.

Mr Lee most likely saw the possibilities for Singapore, including eventually enjoying the world’s highest per-capita income, and becoming a leading business centre for Asia. He would have attributed such success to the confidence of foreign investors drawn to the nation’s amicable industrial relations.

Former President S R Nathan remembers Mr Lee’s focused approach: “He emphasised that his duty was to find ways and means of getting more jobs for people, and it was also the duty of the labour movement to help their fellow workers find jobs. And so for that, we needed industrial peace and a certain balance, not exploitation.”

GETTING THINGS DONE

The National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) was formed in 1961 when the PAP split. Led by Mr Devan Nair, a founding member of the PAP, the NTUC led Singapore’s labour movement away from militant trade unionism to one marked by cooperation.

This made Singapore the first in the world to have a tripartite arrangement where workers, employers and the Government came together to discuss general wage levels. This cooperation contributed significantly to harmonious labour relations and, ultimately, to Singapore’s rapid development in the 1970s and 1980s.

Mr Lee firmly believed that growth and development of the country was in the best interests of the workers and their unions. Speaking in 2011, he said: “In other words, growth is meaningless unless it is shared by the workers, shared not directly in wage increases, but indirectly in better homes, better schools, better hospitals, better playing fields, a healthier environment for their families, and for their children to grow up.”

Singapore’s metamorphosis from mudflat to metropolis was not just a physical transformation. Equally remarkable was the transformation of the psyche of an entire population. Within the span of a few decades, Singaporeans came to be seen as a people who could get things done.

Mr Lee played a big part in that change. From the start, he set the pace for excellence. He once told senior civil servants: “I want to make sure every button works, and if it doesn’t when I happen to be around, then somebody is going to be in for a rough time, because I do not want sloppiness.”

Sprucing up a young nation however was not so straightforward. Besides the challenge of ensuring sufficient security for the country’s borders, Mr Lee and his team had a more fundamental problem to tackle – that of a housing crisis.

HOUSING A NATION

Today, the 50-storey Pinnacle on Cantonment Road stands as an icon in Singapore’s 50-year-old public housing landscape. It is built on the site of one of the earliest public housing projects in the country. But housing in the 1950s was a far cry from what it is today. Slums were common when Singapore achieved self-government in 1959, and there was a full-blown housing crisis.

To meet the nation’s acute housing shortage, the PAP set up the Housing and Development Board in 1960. The aim set for it was to build 10,000 homes a year.

Its predecessor – the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) – was highly sceptical that the new board would meet its ambitious target. The SIT itself had built only 20,000 flats in its entire 30-year history.

The stakes were high and the difficulties daunting. The PAP, which had just come into power, needed to deliver results fast and gain the trust and confidence of Singaporeans.

There was doubt even with the Government of whether the HDB could get the job done, and a committee was set up to find out if the board had the capability and the materials to complete 10,000 houses as planned. When the committee published its report, the HDB had already completed 10,000 units of housing.

The HDB’s performance was crucial to the PAP’s re-election in 1963.

But it was more than a question of providing affordable homes for the people. The social motive to do this was equally compelling, and public housing helped tighten the weave of Singapore’s social fabric.

Mr Lee felt that it was important to have a rooted population. He said in 2010: “If you ask people to defend all the big houses where the bosses live, and they live in harbours, I don’t think that’s tenable. So we decided from the very beginning that everybody must have a home, every family will have something to defend, and that home must be owner-owned, but they have to pay by instalments over 20, 25, even 30 years. And that home we developed over the years into their most valuable asset.”

Today, more than 80 per cent of Singaporeans now live in subsidised public flats that they can call their own.

Singaporeans now had a personal stake in their country that went beyond feelings of patriotism. They had a physical space they could call home, and a vested interest to defend it.

National Service, aimed at defending the country and ensuring its borders were safe from external aggression, took on a different dimension.

After independence, Singapore was left with just two battalions of the Singapore Infantry Regiment. There was an urgent need to build a substantial defence force. And so National Service was introduced in 1967, with universal conscription making it compulsory for every male Singapore citizen to serve in the armed forces for about two years. It also contributed to promoting racial harmony.

UNIFIED BY LANGUAGE

In multi-racial Singapore, English is the common language used by all races. Mr Lee saw early on that English would be a unifier that would give Singapore an edge in the international arena.

But he also believed that knowing one’s mother tongue would build a sense of belonging to one’s roots, and increase self-confidence and self-respect. And so he championed bilingualism.

In retrospect, Mr Lee said that bilingualism was his most difficult policy to implement. He later admitted he had been wrong to assume that one could be equally fluent in two languages. He said in 2004: “Had I known all the difficulties of bilingualism in 1965, as I know now today, would I have done differently? Yes, in its implementation, but not in its policy. I don’t regret the stress and heavy burdens I put, because the other way would have been a destruction of the chance of building up some form of culture worth preserving.”

Former senior minister of state Ch’ng Jit Koon lauded Mr Lee’s foresight in creating a bilingual society. “If he did not succeed in bringing through our education system based on bilingual education, we will not have the advantage among other countries to tap on China’s economic trade,” he said in 2008.

Indeed, Mr Lee and his team were very sensitive to issues involving race, knowing how combustible such matters could be. The formative years of the PAP, the battles against communism and extremism and the racial riots he lived through meant that Mr Lee never underestimated the potentially explosive nature of race relations.

When it was time to remove the small, dilapidated mosques built on state land, he did so with caution. His plan was to replace these “suraus” with bigger and better mosques in every housing estate through voluntary contributions from the Malay-Muslim community, creating a sense of ownership and pride.

Mr Lee also took special interest in ensuring that Singapore’s different communities would all have a share in its prosperity. He believed better education was one of the keys to uplifting the Malay community.

Cabinet minister K Shanmugam said it would have been easy for politicians in Singapore to appeal to the sentiments of the majority Chinese community to gain political power. But he felt that part of the success of Singapore is due to leaders like Mr Lee, who shunned racial politics.

In an earlier interview in 2003, Mr Shanmugam said: “I think most sensible people in the Indian community, particularly those who went through the earlier struggles, who are older than me, accepted this – that we have the space and we have far more liberty and opportunity in Singapore than we would have if we were 6 per cent in any other society, including India, where many of the so-called upper caste Indians in Singapore would not have had a chance.”

Mr Lee Hsien Loong said that the elder Mr Lee remembered the situation that had existed in Malaysia before Singapore became an independent state. “After we became independent, a point that he always reiterated was – never do to the minorities in Singapore that which happened to us when we were a minority in Malaysia. Always make sure that the Malays, the Indians have their space, can live their way of life, and have full equal opportunities and are not discriminated against. And at the same time, help them to upgrade, improve, move forward,” he said in 2013.

CLEAN AND GREEN

Singapore is widely known for being a clean city, both in terms of its environment as well as governance. It is the least corrupt country in Asia, and according to the World Bank, it is one of the most preferred places in the world to do business.

But it was not always graft-free. Corruption was widely prevalent when Singapore was still a British colony. In the 1959 election, the PAP, then the opposition, campaigned against the Government’s corrupt practices. Mr Lee said at the time: “I am convinced that we will thrive and flourish, provided there is an honest and effective Government here.”

The PAP’s anti-corruption position resonated well with the voters. When the PAP Government took office, Mr Lee and his team turned up in all-white as a promise to the people that their leaders will not stand for corruption and will be “whiter than white”.

Over the years, the leadership’s zero tolerance for corruption earned Singapore a reputation for having a clean and effective Government. Establishing rule of law, public security and safety were fundamental to the success of the PAP.

Mr Lee applied the effort to stay clean to the island’s physical transformation as well. From the outset, he was adamant that urban development in the country did not proceed haphazardly. He had seen how a lack of planning had marred other cities, and was determined that Singapore did not make the same mistake.

Observers say this focus on paving the foundation for Singapore to have a first world environment while becoming a first world economy led to the good environment actually becoming an economic asset. And some felt that the efforts to green Singapore gave a certain softness and calmness to the country, and was not just an aesthetic benefit but spoke to the soul of Singaporeans.

Mr Lee expressed his passion for greening Singapore in practical ways. He planted a tree every year, a tradition he started in 1963. This kicked off an island-wide tree-planting initiative and launched Tree Planting Day, a national campaign that helped Singapore earn its reputation as a Garden City.

Mr Lee wrote in his memoirs: “After independence, I searched for some dramatic way to distinguish Singapore from other Third World countries and settled for a clean and green Singapore. Greening is the most cost-effective project I have launched.”

Mr Lee’s original vision of a Garden City evolved over the years into the concept of a City in a Garden, with about 2 million trees planted around the island.

In June 2012, this transformation was celebrated with the opening of the Gardens by the Bay.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said this was just one example of how Singapore’s living environment is being transformed. “It may be a densely populated city, maybe one of the densest in the world, but we are determined that our people should be able to live comfortably, pleasantly, graciously. Not just good homes, efficient public transport or safe streets, but also be in touch with nature, never far from green spaces and blue waters,” he said in 2012.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew was not known to be sentimental about buildings or landmarks, and he was practical yet ambitious about transforming the nation’s landscape, even when it came to defying nature.

And one of his most important initiatives started in 1977, and involved the Singapore River – historically the lifeblood of the economy and the centre of commercial activity.

The river had been the conduit for Singapore’s entrepot trade, allowing for the movement of goods from the port to the city. Over the years, it had degenerated into a filthy, congested, polluted waterway. The industries along its banks had been dumping sewage and garbage into its waters. The water was badly polluted and caused a stench in the area.

Mr Lee’s proposal was perceived as a monumental feat: A clean-up of the entire river.

The rebirth of the Singapore River took 10 years to complete, and today, it is not only glistening again, but its banks are also bustling with trendy restaurants, clubs and offices, and fish have even returned.

The Singapore River, now part of the Marina reservoir, is a constant reminder of the man who defied time and tide. Its transformation mirrors the fascinating evolution of a small backwater into a thriving global metropolis, and its currents echo the ebb and flow of one man’s life as he turned an impossible dream into reality.

In Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s own words: “You begin your journey not knowing where it will take you. You have plans, you have dreams, but every now and again you have to take uncharted roads, face impassable mountains, cross treacherous rivers, be blocked by landslides and earthquakes. That’s the way my life has been.”