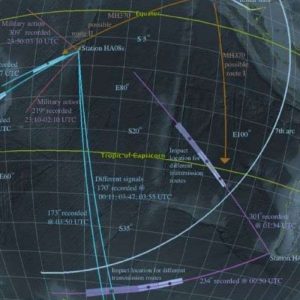

A study of underwater sound waves recorded on the day the Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 disappeared suggests a different route and a possible crash site north-east of Madagascar, if indeed the data is from the missing plane.

Scientists at Cardiff University in the UK have examined acoustic-gravity waves picked up by two hydroacoustic stations in the Indian Ocean, one off Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia and the other at Diego Garcia further north.

Each of the two stations, operated by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organisation, has three “hydrophones” or underwater microphones, which continuously record sound waves in the ocean.

Signals from both stations show sound waves that could have come from a large object, such as a meteorite or an aircraft hitting the water.

Previous studies by both Cardiff University and Curtin University in Western Australia have mostly looked at signals from the Cape Leeuwin station between 12:00am and 2:00am UTC on March 8, 2014, which covers the timeframe when authorities believe the plane crashed, based on satellite data from the plane.

But a new understanding of how fast and far acoustic-gravity waves travel under water led the Cardiff scientists to examine signals over a wider timeframe — from 11:00pm on March 7, 2014 to 4:00am the next day — and include data from the more distant hydroacoustic station at Diego Garcia.

“We have now been able to identify two locations where the aeroplane could have impacted with the ocean, as well as an alternative route that the plane may have taken,” Cardiff University’s Dr Usama Kadri said.

New findings point to Madagascar

An analysis of acoustic waves picked up by the station in Western Australia would suggest a crash site in the southern Indian Ocean that largely includes an area already covered by previous searches for MH370.

But signals from the Diego Garcia station — if indeed they are from the missing aircraft — would indicate a crash site much further north than originally suspected, and mean the missing aircraft must have taken a different route to the one long assumed.

Authorities have long thought the plane crashed somewhere south-west of Western Australia.

The two searches conducted so far have failed to find it.

Dr Kadri said the new findings were based on a better understanding of “sea floor elasticity” or flexibility, which affects how sound waves travel underwater.

“Our research into these waves has moved on since we first proposed the idea in 2017,” Dr Kadri wrote in The Conversation.

“Previous analysis considered the sea floor to be rigid, which would not allow the radiating waves to move through it.

“However, if the elasticity of the sea floor is taken into account, then the waves will travel at this enhanced speed.

“When acoustic-gravity waves start travelling through the sea floor their propagation speed boosts to over 3,500 m/s, from the 1,500m/s they would have been travelling at through the water.”

Allowing for this sea floor elasticity, the site of impact would be much further away from the hydrophone station than previously thought.

Thus, data from the Diego Garcia would point to a crash site north-east of Madagascar, if the signals are from the missing aircraft.

And it is a big if.

Calls for further analysis

Dr Kadri said the sound signals from this northern hydroacoustic station were distorted by “noise” believed to have been caused by a military exercise, known to have been in place around the time on that side of the Indian Ocean.

He said it is feasible that these large sound waves may instead have come from a rocket or missile being fired, rather than a Boeing 777 crashing into the ocean.

“The bearings of some of these signals fall within the area where signals from the military action were picked up, so it is possible that the signals are associated with the military action,” Dr Kadri said.

“But if the signals are related to MH370, this would suggest a new possible impact location in the northern part of the Indian Ocean.”

Inexplicably, 25 minutes of data from the Diego Garcia station — where the US has a secretive military base — is missing.

Dr Kadri said the signals his team analysed indicated a 25-minute shutdown that cannot be explained by a technical failure or maintenance, given the three hydrophones operate independently of each other.

He said the CTBTO has failed to give any reason why the data is missing, though either military action or Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 may have caused the system shutdown.

The Madagascar site is also a long way from the so-called “seventh arc” — the imaginary line that maps possible locations of the aircraft based on satellite signals from the plane that were picked up by Britain’s Inmarsat satellite.

But given there are so many variables in what is known about the plane — including these satellite “pings” — Dr Kadri believes search authorities including Australia should carry out more detailed analysis of the data from both hydroacoustic stations.

“In light of this research we recommended that signals at all times between 23:00 (March 7) and 04:00 (March 8) UTC, at both stations … are analysed with no exception,” he said.

“And that this is done independently from other sources [such as satellite data], to minimise the inclusion of uncertainties related to them.”

Dr Kadri said he has communicated these recommendations to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, which oversaw the first search for MH370 in the Indian Ocean, as well as the MH370 Investigation Team in Malaysia and other relevant authorities, in the hope that the search will resume to find the missing aircraft.

The Cardiff research team also plans to carry out a series of field experiments in the field, to see if they can isolate “hidden signals” in the ambient noise to extract more information from the data picked up by the two hydroacoustic stations.